Importance of training data points: Influence Functions

November 12, 2024 • Rohit, Lucas Laird

Machine learning models learn from data to maximize performance on a given training objective. One intuitive question one might ask is how much does a certain training data point influence the trained model's output on some test input? We could try to answer this question by tackling a counterfactual scenario: What would happen to the model if we removed or modified a certain data point in the training data? The influence of a data point is the amount retraining with that data point removed or perturbed changes the model's parameters compared to training with the original data point. This scheme is called Leave-One-Out(LOO) retraining and it is commonly used as the standard measure of the importance of an individual data point during training. Evaluating LOO over an entire dataset is prohibitively expensive for the massive datasets used in modern ML and retraining can quickly become a major bottleneck as model complexity increases.

Approximating LOO with influence functions

Influence functions are a classic method from statistics proposed by Hampel in 1974 which estimates how much a model's parameters will change when a data point is given higher weight during training. They work by perturbing a data point by a small \(\epsilon\) and calculating the estimated change in the model's parameters as \(I_{\text(up,loss)}\). Influence functions assume a convex loss function (Bae et. al ) and have a closed form solution which can be used to avoid the bottleneck of retraining in LOO. The convexity assumption however is not always satisfied, especially for neural networks. Influence functions also require computing a Hessian which is very expensive for larger models with more parameters.

Koh and Liang test the utility of influence functions for analyzing neural networks despite their non-convexity. To address the expensive Hessian computation, they approximate it using a common numerical computation approach which approximates the Hessian using implicit products. They mitigate the non-convexity issue by creating a quadratic approximation of the loss function which is convex. They calculate \(I_{\text(up,loss)}\) by perturbing a data point by some small \(\epsilon\) and use the quadratic approximation instead of the true loss function. They then modify the model parameters by \(I_{\text(up,loss)}\) which amounts to an euler's method approximation of the change in model parameters. Similarly for non-diffentiable loss functions, they evaluate the utility of using differentiable approximations. Given that Koh and Liang are using convex and differentiable approximations to allow them to use influence functions, will influence functions still give meaningful insights?

Basu et. al evaluate how well influence functions correlate with the actual LOO training for MLPs and CNNs for a variety of model depths, layer widths, and weight decay/L2 regularization. They find that in general the influence functions do not have strong correlation with LOO training and are not effective estimators for neural networks. Despite this, influence functions have been shown to be useful for problems which indirectly require some understanding of data importance. Koh and Liang tested influence empirically on several applications: finding predictively important examples, generating adversarial examples, debugging domain mismatch, and fixing mislabeled or poisoned examples. These experiments show that there is some utility to influence function analysis despite them not consistently approximating LOO training as intended.

Bae et. al try to understand why there is a discrepancy between influence functions and LOO and also if there is something else that they are correlated with. They compared influence functions to LOO along five components: LOO with cold vs. warm starting, proximal regularization of influence, non-converged model parameters, linearization, and approximate linear solving. Through this analysis they also find that influence functions are strongly correlated with a different function called the proximal Bregman response function (PBRF) which estimates the impact of removing a data point but constraining so that outputs for all other training data are minimally impacted.

For LOO training there are two different ways to initialize the model to be retrained. A cold start is when the model is initialized randomly and then trained on the LOO dataset. A warm A warm start is initializing the model parameters to be the parameters found after the original training and then training on the LOO dataset. Typically a cold start is used in LOO but influence functions more closely approximate a warm-start. For smooth and convex loss functions, these two situations are identical but for neural networks there is no guarantee that both cold and warm start LOO will be equivalent. For PRBF, there isn't a cold start version as it enforces that the outputs are similar for other training examples. This makes it more similar to influence functions.

Proximal regularization is a technique used in computing influence functions which uses a damping term which is essentially the quadratic approximation used by Koh and Liang. The damping approximation introduces a small approximation error on the loss function which results in the influence function computing on a proximal warm-start instead of the true warm start. This can be accounted for in PBRF as it also uses a proximal regularization.

In practice models are not trained to true convergence where the loss gradient is zero. This is often done to prevent overfitting and to shorten training time. Due to this, the change in model parameters from warm start LOO retraining reflect the impacts of longer training more than the impacts of removing a data point. The gap between LOO and influence functions caused by this can be accounted for by replacing the loss function with a similar loss function where the model parameters are the true optimal solution. This is done by changing the objective to matching the model's output using the PBRF. This can be thought of as training with labels which are the output of the model.

The last two components come from computing the PBRF. The PBRF is computed using a linearization of the response function which introduces large approximation error when the data point of interest is perturbed more. Additionally these linear equations are solved using linear solvers which themselves can introduce some small error contributing to the discrepancy.

Through their analysis Bae et. al find that the first 3 components contribute the most to the gap between LOO and influence functions. Since those three differences are not present between PBRF and influence functions, they find that influence functions are closely correlated to PBRF with the discrepancy introduced by the last 2 components being orders of magnitude smaller. They suggest that influence functions are not actually suitable for approximating LOO but instead are approximating the PBRF. They find that methods of influence function analysis should be benchmarked with the PBRF instead of LOO.

Studying Large Language Model Generalization with Influence Functions

This work comes from researchers at Anthropic and the University of Toronto led by Roger Grosse and Juhan Bae. The team combines academic expertise in machine learning theory with industry experience in large language model development.

Background & Problem

A key question in understanding large language models (LLMs) is: when a model generates a particular output, is it simply copying training examples or is it creatively combining information in novel ways? Influence functions provide a tool to help answer this by measuring how much individual training examples contribute to specific model behaviors.

However, computing influence functions for large neural networks has been challenging due to two key bottlenecks:

- Computing inverse-Hessian-vector products is very expensive for large models

- Computing gradients for many candidate training examples requires substantial computation

Key Methodological Innovations

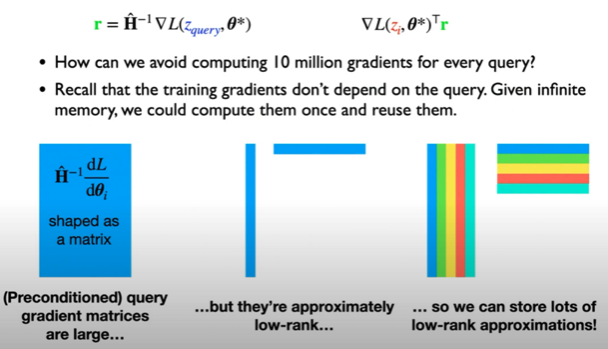

The authors introduce two key techniques to scale influence functions to LLMs with up to 52B parameters:

- Using EK-FAC (Eigenvalue-corrected Kronecker-Factored Approximate Curvature) to efficiently compute inverse-Hessian-vector products

- Query batching to amortize the cost of computing training gradients across multiple influence queries

Key Results

Some of the most interesting findings:

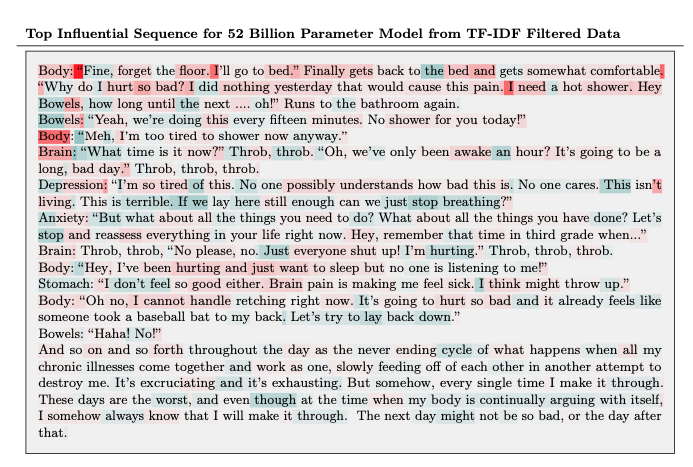

- Larger models show more abstract generalization patterns - their influential training examples tend to be thematically related rather than just having overlapping tokens

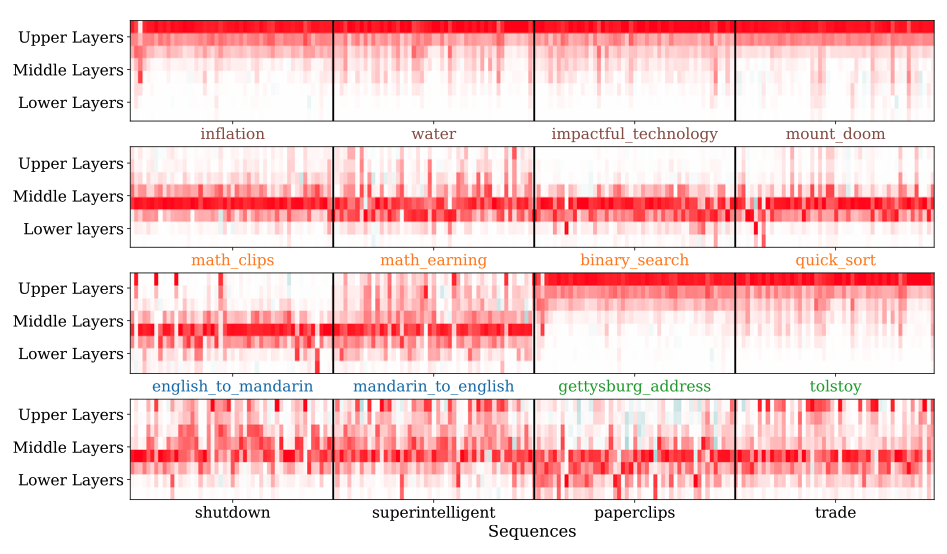

- Influence is distributed throughout the network layers, but different layers show different patterns:

- Upper/lower layers: More focused on surface-level token patterns

- Middle layers: Handle more abstract relationships

- Model outputs appear to come from combining many training examples rather than memorizing just a few sequences

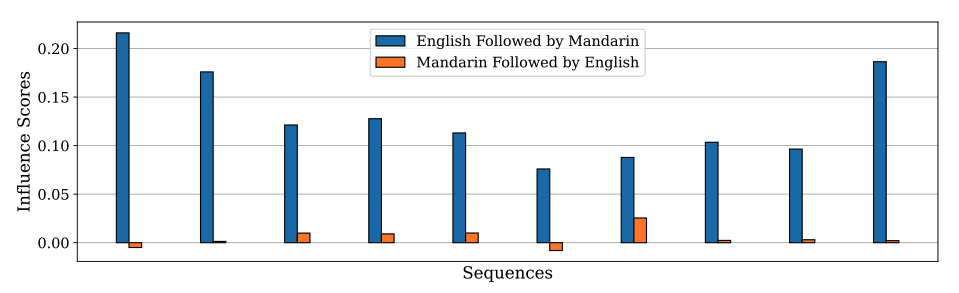

- A surprising limitation: influence decays sharply when key phrases appear in a different order

My Analysis

This paper makes several important contributions to our understanding of LLMs:

Technical Innovation: The scaling up of influence functions is impressive and opens up new possibilities for analyzing large models. The EK-FAC approximation is particularly elegant, providing accurate results while being much more computationally efficient.

Empirical Insights: The finding that larger models show increasingly abstract patterns of influence is fascinating. It provides concrete evidence for how scaling affects model capabilities - not just in terms of raw performance, but in terms of the nature of the generalizations being learned.

Limitations & Future Work: The main limitation is the focus on pretrained models rather than fine-tuned ones. Given how much fine-tuning affects model behavior, extending these techniques to analyze fine-tuning would be a valuable next step. Additionally, the surprising sensitivity to word order suggests there may be fundamental limitations in how these models process information that deserve further study.

Overall, this work represents an important step toward more rigorous and systematic analysis of large language model behavior. The tools developed here will likely prove valuable for future work in model interpretability and alignment.